makemore_BatchNorm¶

Inspired by Andrej Karpathy's "Building makemore Part 3: Activations & Gradients, BatchNorm"

Useful links

- "Kaiming init" paper

- BatchNorm paper

- Bengio et al. 2003 MLP language model paper (pdf)

- Good paper illustrating some of the problems with batchnorm in practice

Table of Contents¶

- 0. Makemore: Introduction

- 1. Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) Internals

- 2. Visualizations

- 3.

BatchNorm: Visualizations - 4.

BatchNorm: Overall Summary - 5. Conclusion

Appendix¶

Figures¶

- A1. Graph of

tanh(x)from x=-4 to x=4. - A2. Graph of the derivative of

tanh(x)from x=-4 to x=4. - A3. Batch Normalization Algorithm.

- A4. ResNet-34 Architecture.

- A5. ResNet Bottleneck Unit Building Block.

Definitions/Explanations¶

- B1. Vanishing/Exploding Gradient Problem

- B2. Batch Normalization: Momentum Factor for Running Parameters Estimation

Guide¶

- C1. Kaiming Normal Distribution in

PyTorch - C2.

BatchNormForward Pass as a Widget - C3.

Linear: Activation Statistics of Forward & Backward Pass - C4.

Linear+BatchNorm: Activation Statistics of Forward & Backward Pass

Exercises¶

References¶

0. Makemore: Introduction¶

Makemore takes one text file as input, where each line is assumed to be one training thing, and generates more things like it. Under the hood, it is an autoregressive character-level language model, with a wide choice of models from bigrams all the way to a Transformer (exactly as seen in GPT). An autoregressive model specifies that the output variable depends linearly on its own previous values and on a stochastic term (an imperfectly predictable term). For example, we can feed it a database of names, and makemore will generate cool baby name ideas that all sound name-like, but are not already existing names. Or if we feed it a database of company names then we can generate new ideas for a name of a company. Or we can just feed it valid scrabble words and generate english-like babble.

"As the name suggests, makemore makes more."

This is not meant to be too heavyweight of a library with a billion switches and knobs. It is one hackable file, and is mostly intended for educational purposes. PyTorch is the only requirement.

Current implementation follows a few key papers:

- Bigram (one character predicts the next one with a lookup table of counts)

- MLP, following Bengio et al. 2003

- CNN, following DeepMind WaveNet 2016 (in progress...)

- RNN, following Mikolov et al. 2010

- LSTM, following Graves et al. 2014

- GRU, following Kyunghyun Cho et al. 2014

- Transformer, following Vaswani et al. 2017

In the 2nd makemore tutorial notebook, we implemented a multilayer perceptron (MLP) character-level language model (a neural probabilistic language model) that used a distributed representation for words to fight the curse of dimensionality issue with n-gram models so as to enable easier and more effective generalization. The model is a 3 layer perceptron. The three layers are: an input layer that converts the input to embeddings using a lookup table, a hidden layer with tanh non-linearity, and an output layer that converts the output of the hidden layer to probabilities.

In this notebook, we dive into some of the internals of that MLP model with multiple layers and scrutinize the statistics of the forward pass activations, backward pass gradients, and some of the pitfalls when they are improperly scaled. We also look at the typical diagnostic tools and visualizations you'd want to use to understand the health of your deep network. We learn why training deep neural nets can be fragile and introduce the first modern innovation that made doing so much easier: Batch Normalization. Residual connections and the Adam optimizer remain notable todos for later video.

import torch

import torch.nn.functional as F

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # for making figures

%matplotlib inline

# read in all the words

words = open('../data/names.txt', 'r').read().splitlines()

words[:8]

['emma', 'olivia', 'ava', 'isabella', 'sophia', 'charlotte', 'mia', 'amelia']

len(words)

32033

# build the vocabulary of characters and mappings to/from integers

chars = sorted(list(set(''.join(words))))

stoi = {s:i+1 for i,s in enumerate(chars)}

stoi['.'] = 0

itos = {i:s for s,i in stoi.items()}

vocab_size = len(itos)

print(itos)

print(vocab_size)

{1: 'a', 2: 'b', 3: 'c', 4: 'd', 5: 'e', 6: 'f', 7: 'g', 8: 'h', 9: 'i', 10: 'j', 11: 'k', 12: 'l', 13: 'm', 14: 'n', 15: 'o', 16: 'p', 17: 'q', 18: 'r', 19: 's', 20: 't', 21: 'u', 22: 'v', 23: 'w', 24: 'x', 25: 'y', 26: 'z', 0: '.'}

27

# build the dataset

block_size = 3 # context length: how many characters do we take to predict the next one?

def build_dataset(words):

X, Y = [], []

for w in words:

context = [0] * block_size

for ch in w + '.':

ix = stoi[ch]

X.append(context)

Y.append(ix)

context = context[1:] + [ix] # crop and append

X = torch.tensor(X)

Y = torch.tensor(Y)

print(X.shape, Y.shape)

return X, Y

import random

random.seed(42)

random.shuffle(words)

n1 = int(0.8*len(words))

n2 = int(0.9*len(words))

Xtr, Ytr = build_dataset(words[:n1]) # 80%

Xdev, Ydev = build_dataset(words[n1:n2]) # 10%

Xte, Yte = build_dataset(words[n2:]) # 10%

torch.Size([182625, 3]) torch.Size([182625]) torch.Size([22655, 3]) torch.Size([22655]) torch.Size([22866, 3]) torch.Size([22866])

# MLP

n_embd = 10 # the dimensionality of the character embedding vectors

n_hidden = 200 # the number of neurons in the hidden layer of the MLP

g = torch.Generator().manual_seed(2147483647) # for reproducibility

C = torch.randn((vocab_size, n_embd), generator=g)

W1 = torch.randn((n_embd * block_size, n_hidden), generator=g)

b1 = torch.randn(n_hidden, generator=g)

W2 = torch.randn((n_hidden, vocab_size), generator=g)

b2 = torch.randn(vocab_size, generator=g)

parameters = [C, W1, b1, W2, b2]

print(sum(p.nelement() for p in parameters)) # number of parameters in total

for p in parameters:

p.requires_grad = True

11897

# same optimization as last time

max_steps = 200000

batch_size = 32

lossi = []

for i in range(max_steps):

# minibatch construct

ix = torch.randint(0, len(Xtr), (batch_size,), generator=g)

Xb, Yb = Xtr[ix], Ytr[ix] # batch X, Y

# forward pass

emb = C[Xb] # embed characters into vector space

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # flatten (concatenate the vectors)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # hidden layer pre-activation

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # hidden layer activation

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # output layer

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, Yb) # cross-entropy loss function

# backward pass

for p in parameters:

p.grad = None

loss.backward()

# update

lr = 0.1 if i < 100000 else 0.01 # step learning rate decay

for p in parameters:

p.data -= lr * p.grad

# track stats

if i % 10000 == 0: # print every once in a while

print(f'{i:7d}/{max_steps:7d}: {loss.item():.4f}')

lossi.append(loss.log10().item())

0/ 200000: 27.8817 10000/ 200000: 2.8967 20000/ 200000: 2.5186 30000/ 200000: 2.7832 40000/ 200000: 2.0202 50000/ 200000: 2.4007 60000/ 200000: 2.4256 70000/ 200000: 2.0593 80000/ 200000: 2.3780 90000/ 200000: 2.3469 100000/ 200000: 1.9764 110000/ 200000: 2.3074 120000/ 200000: 1.9807 130000/ 200000: 2.4783 140000/ 200000: 2.2580 150000/ 200000: 2.1702 160000/ 200000: 2.0531 170000/ 200000: 1.8323 180000/ 200000: 2.0267 190000/ 200000: 1.8685

plt.plot(lossi)

plt.show()

@torch.no_grad() # this decorator disables gradient tracking

def split_loss(split):

x,y = {

"train": (Xtr, Ytr),

"dev": (Xdev, Ydev),

"test": (Xte, Yte),

}[split]

emb = C[x] # (N, block_size, n_embd)

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # (N, block_size * n_embd)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # (N, n_hidden)

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # (N, n_hidden)

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # (N, vocab_size)

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, y)

print(f"{split} loss: {loss.item()}")

split_loss("train")

split_loss("dev")

train loss: 2.1240577697753906 dev loss: 2.165454626083374

# sample from the model

g = torch.Generator().manual_seed(2147483647 + 10)

for _ in range(20):

out = []

context = [0] * block_size # initialize with all ...

while True:

# forward pass the neural net

emb = C[torch.tensor([context])] # (1,block_size,n_embd)

x = emb.view(emb.shape[0], -1) # concatenate the vectors

h = torch.tanh(x @ W1 + b1)

logits = h @ W2 + b2

probs = F.softmax(logits, dim=1)

# sample from the distribution

ix = torch.multinomial(probs, num_samples=1, generator=g).item()

# shift the context window and track the samples

context = context[1:] + [ix]

out.append(ix)

# if we sample the special '.' token, break

if ix == 0:

break

print(''.join(itos[i] for i in out)) # decode and print the generated word

carpah. amorie. khirmy. xhetty. salayson. mahnen. den. art. kaqui. nellaiah. maiir. kaleigh. ham. jorn. quintis. lilea. jadii. wazelo. dearyn. kai.

1.1. Fixing the Initial Loss¶

We can tell that out network is very improperly configured at initialization. We can tell the initialization is bad because the first/zeroth iteration loss is extremely high.

In neural network training, it's very likely that we have a rough idea of what loss to expect at initialization and that depends on the loss function and the problem set-up.

In our case, we don't expect an initialization training loss of $\boldsymbol{27}$, we expect a much lower number which we can calculate.

At initialization, there are 27 characters that could be predicted next for any single training example. At initialization, each character is equally likely therefore we would expect a uniform distribution - of predicted probabilities - assigning about equal probability to all the 27 characters (1/27.0 ~= 3.7%).

$$\\{logits}_{ij} = \frac{e^{C_{ij}}}{\sum_{j} e^{C_{ij}}} = \frac{C}{27C} = \frac{1}{27}$$

expected_loss = - torch.tensor(1 / 27).log()

print(expected_loss)

tensor(3.2958)

The expected loss is $\boldsymbol{3.29}$ which is much lower than $\boldsymbol{27}$. This is because at initialization the neural net is creating probability distributions that are all messed up. Some characters are very confident while some characters are very non-confident. So essentially, the network is very confidently wrong which leads to a very high loss. Our loss is high because our network, rather arbitrarily, assigns very high probabilities to the incorrect label (or low probability to the correct label). Below, let's go through a smaller 4-D example of the issue.

# 4-dimensional example of the issue

logits = torch.tensor([1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0])

#logits = torch.rand(4) * 10

probs = torch.softmax(logits, dim=0)

loss = -1 * torch.log(probs[2])

#loss = -probs[2].log()

logits, probs, loss

(tensor([1., 1., 1., 1.]), tensor([0.2500, 0.2500, 0.2500, 0.2500]), tensor(1.3863))

The high value of the loss function during the first iteration of our network indicates that the network was not initialized correctly. Since we have no information to indicate that one character is more likely to be better than others, it is reasonable to assume that the initial probability distribution is uniform. To achieve this, it is necessary for the logits to be approximately zero when the network is initialized.

Reminder: the probabilities are obtained by passing logits through the softmax function

But we need to initialize not the logits, but the weights and biases. How should they be initialized to get zero logits? One approach is to set all biases to zero and scale down a (normal) distribution of weights by a small factor, such as 0.01. However, we usually don’t set the weights exactly to zero (we want some symmetry breaking), as this can slow down the optimization process.

For our case, let's scale W2 = W2 * 0.01 & b2 = b2 * 0 to get the logits to be closer to zero and therefore prevent our network from being very confidently wrong.

# MLP revisited

n_embd = 10 # the dimensionality of the character embedding vectors

n_hidden = 200 # the number of neurons in the hidden layer of the MLP

g = torch.Generator().manual_seed(2147483647) # for reproducibility

C = torch.randn((vocab_size, n_embd), generator=g)

W1 = torch.randn((n_embd * block_size, n_hidden), generator=g)

b1 = torch.randn(n_hidden, generator=g)

W2 = torch.randn((n_hidden, vocab_size), generator=g) * 0.01

b2 = torch.randn(vocab_size, generator=g) * 0

parameters = [C, W1, b1, W2, b2]

print(sum(p.nelement() for p in parameters)) # number of parameters in total

for p in parameters:

p.requires_grad = True

11897

# same optimization as last time

max_steps = 200000

batch_size = 32

lossi = []

for i in range(max_steps):

# minibatch construct

ix = torch.randint(0, len(Xtr), (batch_size,), generator=g)

Xb, Yb = Xtr[ix], Ytr[ix] # batch X, Y

# forward pass

emb = C[Xb] # embed characters into vector space

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # flatten (concatenate the vectors)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # hidden layer pre-activation

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # hidden layer activation

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # output layer

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, Yb) # cross-entropy loss function

# backward pass

for p in parameters:

p.grad = None

loss.backward()

# update

lr = 0.1 if i < 100000 else 0.01 # step learning rate decay

for p in parameters:

p.data -= lr * p.grad

# track stats

if i % 10000 == 0: # print every once in a while

print(f'{i:7d}/{max_steps:7d}: {loss.item():.4f}')

lossi.append(loss.log10().item())

0/ 200000: 3.3221 10000/ 200000: 2.1900 20000/ 200000: 2.4196 30000/ 200000: 2.6067 40000/ 200000: 2.0601 50000/ 200000: 2.4988 60000/ 200000: 2.3902 70000/ 200000: 2.1344 80000/ 200000: 2.3369 90000/ 200000: 2.1299 100000/ 200000: 1.8329 110000/ 200000: 2.2053 120000/ 200000: 1.8540 130000/ 200000: 2.4566 140000/ 200000: 2.1879 150000/ 200000: 2.1118 160000/ 200000: 1.8956 170000/ 200000: 1.8644 180000/ 200000: 2.0326 190000/ 200000: 1.8417

plt.plot(lossi)

plt.show()

The training loss plot doesn't have a hockey stick shape anymore because in the hockey stick, for the very first few iterations of the loss, the optimization is squashing down the logits and then rearranging them. But now, we took away the easy part of the loss function where the weights were just being shrunk down and so therefore we don't get these easy gains in the beginning, instead we just get the hard gains of training the actual neural network, and therefore there's no hockey stick appearance.

@torch.no_grad() # this decorator disables gradient tracking

def split_loss(split):

x,y = {

"train": (Xtr, Ytr),

"dev": (Xdev, Ydev),

"test": (Xte, Yte),

}[split]

emb = C[x] # (N, block_size, n_embd)

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # (N, block_size * n_embd)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # (N, n_hidden)

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # (N, n_hidden)

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # (N, vocab_size)

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, y)

print(f"{split} loss: {loss.item()}")

split_loss("train")

split_loss("dev")

train loss: 2.069589138031006 dev loss: 2.131074905395508

With proper initialization of the training loop, the training and validation losses decrease from $\boldsymbol{2.124}$ and $\boldsymbol{2.165}$ to $\boldsymbol{2.069}$ and $\boldsymbol{2.131}$ respectively. This is because proper initialization allows us to spend more time/cycles optimizing the neural network instead of squashing down the weights in the first several thousand iterations. As a result, we don’t have the hockey stick behavior of the loss function at the beginning.

1.2. Fixing the Saturated tanh¶

The next issue we encounter lies in the hidden state activations (tanh function).

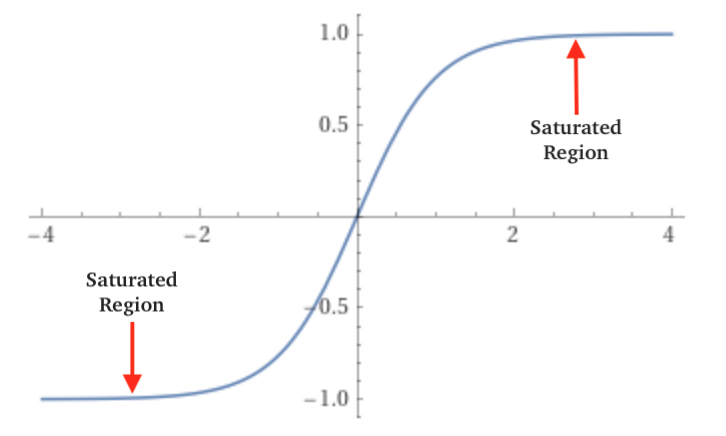

The range of the tanh function is between -1 and 1 and it is zero-centered ($\boldsymbol{-1 < tanh(x) < 1}$). When the pre-activation values (hpreact) become small or large, tanh saturates at -1 and 1. In the saturated region, the rate of change of tanh becomes zero, which hinders effective weight updates as shown in figures 1 & 2 below.

Thus if the pre-activation values lies in the saturating regions as shown in the figures below, then the tanh gradient will become $\boldsymbol{0}$

self.grad += (1-tanh²) * out.grad = (1 - 1) * out.grad = 0.

It has no gradient to propagate. Weights will not be updated effectively.

NewWeight = OldWeight — learningrate * (derivative of error w.r.t weight)

$\boldsymbol{f(x)}$ = 1 which is peak value. $\boldsymbol{f'(x)}$ will be 0.

A neuron is considered saturated when it reaches its peak value. At this point, the derivative of the parameter becomes zero, leading to no updates in the weights. This phenomenon is known as the Vanishing Gradient problem.

To address this, we should maintain pre-activations hpreact = embcat @ (W1) + b1 close to zero, especially during initialization. This can be achieved by scaling down W1 and b1.

Fig. 1: Graph of tanh(x) from x=-4 to x=4. (Source)

Fig. 2: Graph of the derivative of

Fig. 2: Graph of the derivative of tanh(x) from x=-4 to x=4. (Source)

The activation function maps the outputs from the linear layer to a range between -1 and 1. If we plot the distribution of activations, we will observe that most of the activations are either -1 or 1. This is because the distribution of preactivations (the values before being transformed by the activation function) is very broad.

Why is this a problem? During backpropagation, the gradient of the tanh function is proportional to (1 — tanh²). When the value of tanh is close to 1 or -1, the gradient becomes almost zero, which stops the backpropagation through this unit.

Intuitively, it makes sense. In figure 1 above, if you are in the “flat” tail of the tanh curve, changes in the input do not have a significant impact on the output. Therefore, we can change the weights and biases as we want, and this will not affect the loss function. On the other hand, when the output of the tanh function is close to zero, the unit is relatively inactive and the gradient simply passes through without significant impact. In general, the more the output is in the flat regions of the tanh curve, the more the gradient is squashed.

# MLP revisited

n_embd = 10 # the dimensionality of the character embedding vectors

n_hidden = 200 # the number of neurons in the hidden layer of the MLP

g = torch.Generator().manual_seed(2147483647) # for reproducibility

C = torch.randn((vocab_size, n_embd), generator=g)

W1 = torch.randn((n_embd * block_size, n_hidden), generator=g)

b1 = torch.randn(n_hidden, generator=g)

W2 = torch.randn((n_hidden, vocab_size), generator=g) * 0.01

b2 = torch.randn(vocab_size, generator=g) * 0

parameters = [C, W1, b1, W2, b2]

print(sum(p.nelement() for p in parameters)) # number of parameters in total

for p in parameters:

p.requires_grad = True

11897

# same optimization as last time

max_steps = 200000

batch_size = 32

lossi = []

for i in range(max_steps):

# minibatch construct

ix = torch.randint(0, len(Xtr), (batch_size,), generator=g)

Xb, Yb = Xtr[ix], Ytr[ix] # batch X, Y

# forward pass

emb = C[Xb] # embed characters into vector space

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # flatten (concatenate the vectors)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # hidden layer pre-activation

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # hidden layer activation

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # output layer

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, Yb) # cross-entropy loss function

# backward pass

for p in parameters:

p.grad = None

loss.backward()

# update

lr = 0.1 if i < 100000 else 0.01 # step learning rate decay

for p in parameters:

p.data -= lr * p.grad

# track stats

if i % 10000 == 0: # print every once in a while

print(f'{i:7d}/{max_steps:7d}: {loss.item():.4f}')

lossi.append(loss.log10().item())

break

0/ 200000: 3.3221

h

tensor([[ 0.8100, -0.8997, -0.9993, ..., -0.9097, -1.0000, 1.0000],

[-1.0000, -0.9571, -0.7145, ..., 0.4898, 0.9090, 0.9937],

[ 0.9983, -0.3340, 1.0000, ..., 0.9443, 0.9905, 1.0000],

...,

[-1.0000, 0.9604, -0.1418, ..., -0.1266, 1.0000, 1.0000],

[-1.0000, -0.4385, -0.8882, ..., -0.3316, 0.9995, 1.0000],

[-1.0000, 0.9604, -0.1418, ..., -0.1266, 1.0000, 1.0000]],

grad_fn=<TanhBackward0>)

plt.hist(h.view(-1).tolist(), 50);

plt.hist(hpreact.view(-1).tolist(), 50);

When observing hidden layer activations, we can see that most of them are $1$ or $-1$. This is called the saturation of the tanh units. When the outputs of the tanh units are close to $1$ or $-1$, the gradients are close to $0$.

During backpropagation, these saturated units kill the gradient flow. Now let’s observe the distribution of the saturated units. The code below represents neurons with values less than $-0.99$ or greater than $0.99$ as white dots.

# Show the neurons as white dot with value less than -0.99 or greater than 0.99.

#This is a boolean tensor. [statement = h.abs() > 0.99]

#White: statement is true

#Black: statement is false

plt.figure(figsize=(20,10))

plt.imshow(h.abs() > 0.99, cmap = 'gray', interpolation = 'nearest')

plt.title("|h| > 0.99: white is True, black is False")

plt.xlabel("← tensor of length 200 →", labelpad=20, fontdict={"size":15})

plt.ylabel("← total 32 tensors →", labelpad=20, fontdict={"size":15});

Dead neurons refer to neurons that always output either $1$ or $-1$ for the tanh activation function, regardless of the input. Dead neurons are unable to learn and adapt to new data, as their gradients are always zero. This can occur at either the initialization or optimization stage for various types of non-linearities such as tanh, sigmoid, ReLU & ELU with flat tails where the gradients are zero. For example, if the learning rate is too high, a neuron may receive a strong gradient and be pushed out of the data manifold, resulting in a dead neuron that is no longer activated. This can be thought of as a kind of permanent brain damage in the network’s mind.

Some other activations, such as Leaky ReLU, don’t suffer as much from this problem because they don’t have flat tails.

How to identify dead neurons? Forward the examples from the entire training set through the network after training. Neurons that never activate are dead and therefore do not contribute to the learning process.

To address the problem of dead neurons, it is important to keep the preactivations close to zero. One way to do this is to scale the preactivations to limit their range. This can help prevent the gradients from becoming too small or zero, allowing the neuron to continue learning and adapting to new data.

For our case, let's scale W1 = W1 * 0.2 & b1 = b1 * 0.01 to get the hpreact to be closer to zero and therefore minimize the vanishing gradient problem.

# MLP revisited

n_embd = 10 # the dimensionality of the character embedding vectors

n_hidden = 200 # the number of neurons in the hidden layer of the MLP

g = torch.Generator().manual_seed(2147483647) # for reproducibility

C = torch.randn((vocab_size, n_embd), generator=g)

W1 = torch.randn((n_embd * block_size, n_hidden), generator=g) * 0.2

b1 = torch.randn(n_hidden, generator=g) * 0.01

W2 = torch.randn((n_hidden, vocab_size), generator=g) * 0.01

b2 = torch.randn(vocab_size, generator=g) * 0

parameters = [C, W1, b1, W2, b2]

print(sum(p.nelement() for p in parameters)) # number of parameters in total

for p in parameters:

p.requires_grad = True

11897

# same optimization as last time

max_steps = 200000

batch_size = 32

lossi = []

for i in range(max_steps):

# minibatch construct

ix = torch.randint(0, len(Xtr), (batch_size,), generator=g)

Xb, Yb = Xtr[ix], Ytr[ix] # batch X, Y

# forward pass

emb = C[Xb] # embed characters into vector space

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # flatten (concatenate the vectors)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # hidden layer pre-activation

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # hidden layer activation

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # output layer

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, Yb) # cross-entropy loss function

# backward pass

for p in parameters:

p.grad = None

loss.backward()

# update

lr = 0.1 if i < 100000 else 0.01 # step learning rate decay

for p in parameters:

p.data -= lr * p.grad

# track stats

if i % 10000 == 0: # print every once in a while

print(f'{i:7d}/{max_steps:7d}: {loss.item():.4f}')

lossi.append(loss.log10().item())

break

0/ 200000: 3.3135

plt.hist(h.view(-1).tolist(), 50);

plt.hist(hpreact.view(-1).tolist(), 50);

# Show the neurons as white dot with value less than -0.99 or greater than 0.99.

#This is a boolean tensor. [statement = h.abs() > 0.99]

#White: statement is true

#Black: statement is false

plt.figure(figsize=(20,10))

plt.imshow(h.abs() > 0.99, cmap = 'gray', interpolation = 'nearest')

plt.title("|h| > 0.99: white is True, black is False")

plt.xlabel("← tensor of length 200 →", labelpad=20, fontdict={"size":15})

plt.ylabel("← total 32 tensors →", labelpad=20, fontdict={"size":15});

Now Let's run the full training and optimization loop without the break.

# MLP revisited

n_embd = 10 # the dimensionality of the character embedding vectors

n_hidden = 200 # the number of neurons in the hidden layer of the MLP

g = torch.Generator().manual_seed(2147483647) # for reproducibility

C = torch.randn((vocab_size, n_embd), generator=g)

W1 = torch.randn((n_embd * block_size, n_hidden), generator=g) * 0.2

b1 = torch.randn(n_hidden, generator=g) * 0.01

W2 = torch.randn((n_hidden, vocab_size), generator=g) * 0.01

b2 = torch.randn(vocab_size, generator=g) * 0

parameters = [C, W1, b1, W2, b2]

print(sum(p.nelement() for p in parameters)) # number of parameters in total

for p in parameters:

p.requires_grad = True

11897

# same optimization as last time

max_steps = 200000

batch_size = 32

lossi = []

for i in range(max_steps):

# minibatch construct

ix = torch.randint(0, len(Xtr), (batch_size,), generator=g)

Xb, Yb = Xtr[ix], Ytr[ix] # batch X, Y

# forward pass

emb = C[Xb] # embed characters into vector space

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # flatten (concatenate the vectors)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # hidden layer pre-activation

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # hidden layer activation

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # output layer

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, Yb) # cross-entropy loss function

# backward pass

for p in parameters:

p.grad = None

loss.backward()

# update

lr = 0.1 if i < 100000 else 0.01 # step learning rate decay

for p in parameters:

p.data -= lr * p.grad

# track stats

if i % 10000 == 0: # print every once in a while

print(f'{i:7d}/{max_steps:7d}: {loss.item():.4f}')

lossi.append(loss.log10().item())

0/ 200000: 3.3135 10000/ 200000: 2.1648 20000/ 200000: 2.3061 30000/ 200000: 2.4541 40000/ 200000: 1.9787 50000/ 200000: 2.2930 60000/ 200000: 2.4232 70000/ 200000: 2.0680 80000/ 200000: 2.3095 90000/ 200000: 2.1207 100000/ 200000: 1.8269 110000/ 200000: 2.2045 120000/ 200000: 1.9797 130000/ 200000: 2.3946 140000/ 200000: 2.1000 150000/ 200000: 2.1948 160000/ 200000: 1.8619 170000/ 200000: 1.7809 180000/ 200000: 1.9673 190000/ 200000: 1.8295

plt.plot(lossi)

plt.show()

The training loss plot doesn't have a hockey stick shape anymore because in the hockey stick, for the very first few iterations of the loss, the optimization is squashing down the logits and then rearranging them. But now, we took away the easy part of the loss function where the weights were just being shrunk down and so therefore we don't get these easy gains in the beginning, instead we just get the hard gains of training the actual neural network, and therefore there's no hockey stick appearance.

@torch.no_grad() # this decorator disables gradient tracking

def split_loss(split):

x,y = {

"train": (Xtr, Ytr),

"dev": (Xdev, Ydev),

"test": (Xte, Yte),

}[split]

emb = C[x] # (N, block_size, n_embd)

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # (N, block_size * n_embd)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # (N, n_hidden)

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # (N, n_hidden)

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # (N, vocab_size)

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, y)

print(f"{split} loss: {loss.item()}")

split_loss("train")

split_loss("dev")

train loss: 2.0355966091156006 dev loss: 2.1026785373687744

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize = (15, 4))

axes[0].hist(hpreact.flatten().data, bins = 50)

axes[0].set_title("h pre-activation")

axes[1].hist(h.flatten().data, bins = 50)

axes[1].set_title("h")

axes[2].plot(torch.linspace(-5, 5, 100), torch.tanh(torch.linspace(-5, 5, 100)))

axes[2].set_title("tanh");

plt.figure(figsize = (20, 10))

plt.imshow(h.abs() > 0.99, cmap = "gray", interpolation='nearest')

plt.title("|h| > 0.99: white is True, black is False")

plt.xlabel("← tensor of length 200 →", labelpad=20, fontdict={"size":15})

plt.ylabel("← total 32 tensors →", labelpad=20, fontdict={"size":15});

With fixing the saturated tanh function and dead neuron issues, the training and validation losses decreased even further from $\boldsymbol{2.124}$ and $\boldsymbol{2.165}$ to $\boldsymbol{2.035}$ and $\boldsymbol{2.103}$ respectively. This is because the less the output is in the flat regions of the tanh curve, the less the gradient is squashed, and the more gradients are activated and non-zero thereby allowing the neuron to continue actual learning and adapting to new data.

The losses keep reducing because our initialization is better and as such we spend more time doing productive training instead of non-productive training (softmax over-confidence learning and cycles of squahsing down the weight matrix). This shows the impact of initialization on performance solely from considering the MLP internals, activations and gradients.

We're working with a simple 1-layer MLP, which is quite shallow. Because of the shallow nature of the network, the optimization problem is quite easy & very forgiving and this is reflected in the network's ability to still learn eventually despite the terrible initialization (although the result is a bit worse). This is not the general case, especially once we start to work with deeper networks (ex. $50$ layers) because things get more complicated and these issues stack up. Basically, it can get to a point where the network does not train at all if the initialization is bad enough. Essentially, the deeper your network is, the more complex it is and the less forgiving it is to some of these errors. This is a scenario to be cautious and aware of, which you can diagnose/scrutinize by visualizations.

1.3. Calculating the Init Scale: "Kaiming Initialization"¶

We need a defined semi-principled methodology that govern the scaling of the initialization sizes (weights and biases) rather than picking arbitrarily small numbers so things can be predefined and set for large neural networks with a lot of layers.

- How much should we limit the sizes of the initialization?

- Where did the scale factors ($\boldsymbol{0.01}$, $\boldsymbol{0.1}$, $\boldsymbol{0.2}$) come from in initializing the weights and biases?

x = torch.randn(1000,10)

W = torch.randn(10,200) / 10**0.5

y = x @ W

print(x.mean(),x.std())

print(y.mean(),y.std())

plt.figure(figsize =(20,5))

plt.subplot(121)

plt.hist(x.view(-1).tolist(),50,density = True)

plt.subplot(122)

plt.hist(y.view(-1).tolist(),50, density = True);

tensor(-0.0085) tensor(0.9879) tensor(-0.0006) tensor(0.9880)

- How do we scale the weights to preserve the gaussian distribution (

mean = 0&std_dev = 1) from X in Y? - More specifically, what scaling factor do we apply to the weights to preserve the standard deviation of 1 (

std_dev = 1) ?

Standard deviation and weights scaling

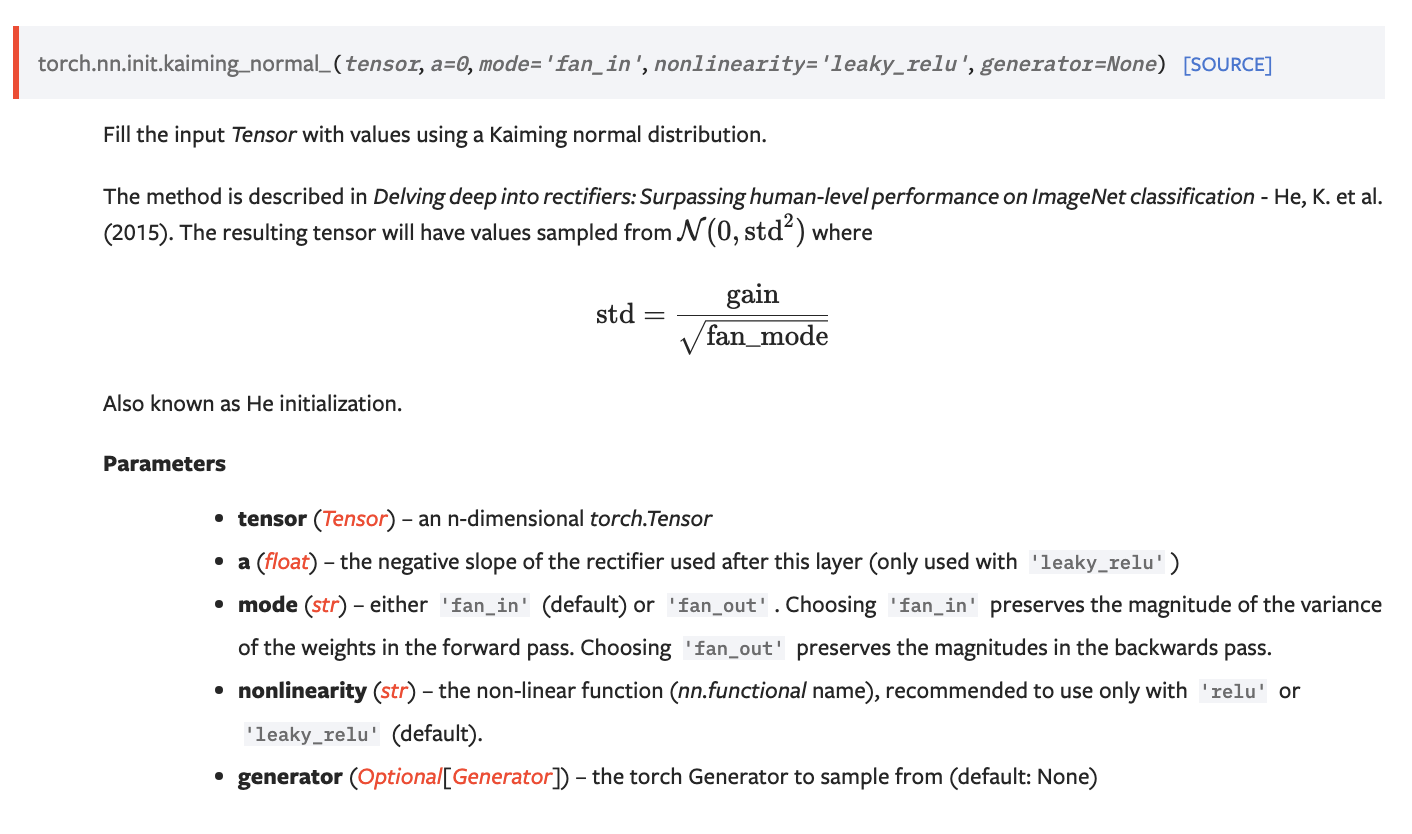

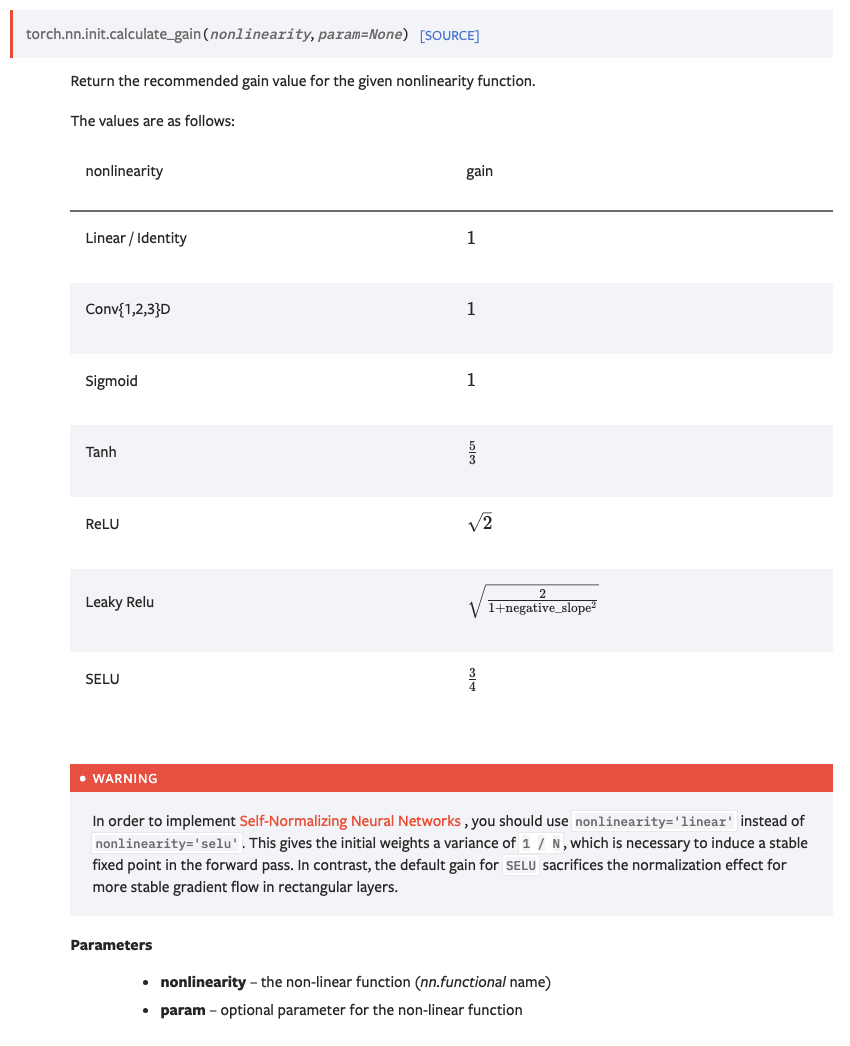

When we pass the input X through a linearity with weights W, the standard deviation of the output Y = W*X changes (increase or decrease) depending on the values of the weights. In order to maintain relatively similar activations throughout the neural network, it is important to scale the weights in a way that preserves the standard deviation of the output at a value of 1. One method for doing this is to follow the Kaiming He et. al. paper, which recommends dividing the weights by the square root of fan_in (num. of inputs) or fan_out (num. of outputs) and multiplying by the gain function. The implementation of the Kaiming normal distribution can be found in Pytorch.

Why do we need gain on top of the initialization? All non-linearities are contractive transformations, which means they “squeeze” the data and reduce the standard deviation. To counter this effect, it is necessary to “boost” the weights slightly using a gain function. By scaling the weights in this manner, we can ensure that the standard deviation of the output is not affected by the scaling.

Modern innovations have made neural networks less fragile (~9 yrs ago, more finicky initializations, need for precision and care in handling activations & gradients, $-$ their ranges, their histograms $-$ gains, non-linearities), significantly more stable and more well-behaved, and thus exact network initializations have become less important. Some of these modern innovations are:

- residual connections

- the use of a number of normalization layers

- batch normalization

- group normalization

- layer normalization

- much better optimizers

- RMSprop

- Adam

(torch.randn(10000) * 0.2).std()

tensor(0.2014)

(5/3) / (30**0.5)

0.3042903097250923

torch.nn.init.calculate_gain('tanh')

1.6666666666666667

The Kaiming Initialization scaling factor for the tanh function using the equation above is

$$

\\Std = \frac{gain}{\sqrt{{fan}_{mode}}} = \frac{{gain}_{\tanh}}{\sqrt{{fan}_{in}}} = \frac{{gain}_{\tanh}}{\sqrt{{n}_{embd}\times{block}_{size}}} =

\frac{5/3}{\sqrt{10\times3}}

$$

where

fan_mode=fan_in=n_embd * block_size(default of ${fan}_{mode}$ is ${fan}_{in}$)gain=torch.nn.init.calculate_gain('tanh')=5/3std=gain/sqrt(fan_mode)=(5/3) / (30**0.5)

# MLP revisited

n_embd = 10 # the dimensionality of the character embedding vectors

n_hidden = 200 # the number of neurons in the hidden layer of the MLP

g = torch.Generator().manual_seed(2147483647) # for reproducibility

C = torch.randn((vocab_size, n_embd), generator=g)

W1 = torch.randn((n_embd * block_size, n_hidden), generator=g) * (5/3) / ((n_embd * block_size)**0.5)

b1 = torch.randn(n_hidden, generator=g) * 0.01

W2 = torch.randn((n_hidden, vocab_size), generator=g) * 0.01

b2 = torch.randn(vocab_size, generator=g) * 0

parameters = [C, W1, b1, W2, b2]

print(sum(p.nelement() for p in parameters)) # number of parameters in total

for p in parameters:

p.requires_grad = True

11897

# same optimization as last time

max_steps = 200000

batch_size = 32

lossi = []

for i in range(max_steps):

# minibatch construct

ix = torch.randint(0, len(Xtr), (batch_size,), generator=g)

Xb, Yb = Xtr[ix], Ytr[ix] # batch X, Y

# forward pass

emb = C[Xb] # embed characters into vector space

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # flatten (concatenate the vectors)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # hidden layer pre-activation

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # hidden layer activation

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # output layer

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, Yb) # cross-entropy loss function

# backward pass

for p in parameters:

p.grad = None

loss.backward()

# update

lr = 0.1 if i < 100000 else 0.01 # step learning rate decay

for p in parameters:

p.data -= lr * p.grad

# track stats

if i % 10000 == 0: # print every once in a while

print(f'{i:7d}/{max_steps:7d}: {loss.item():.4f}')

lossi.append(loss.log10().item())

0/ 200000: 3.3179 10000/ 200000: 2.1910 20000/ 200000: 2.3270 30000/ 200000: 2.5396 40000/ 200000: 1.9468 50000/ 200000: 2.3331 60000/ 200000: 2.3852 70000/ 200000: 2.1173 80000/ 200000: 2.3159 90000/ 200000: 2.2010 100000/ 200000: 1.8591 110000/ 200000: 2.0881 120000/ 200000: 1.9389 130000/ 200000: 2.3913 140000/ 200000: 2.0949 150000/ 200000: 2.1458 160000/ 200000: 1.7824 170000/ 200000: 1.7249 180000/ 200000: 1.9752 190000/ 200000: 1.8614

plt.plot(lossi)

plt.show()

@torch.no_grad() # this decorator disables gradient tracking

def split_loss(split):

x,y = {

"train": (Xtr, Ytr),

"dev": (Xdev, Ydev),

"test": (Xte, Yte),

}[split]

emb = C[x] # (N, block_size, n_embd)

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # (N, block_size * n_embd)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # (N, n_hidden)

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # (N, n_hidden)

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # (N, vocab_size)

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, y)

print(f"{split} loss: {loss.item()}")

split_loss("train")

split_loss("dev")

train loss: 2.0376644134521484 dev loss: 2.106989622116089

With kaiming initialization, the training and validation losses decreased even further from $\boldsymbol{2.124}$ and $\boldsymbol{2.165}$ to $\boldsymbol{2.037}$ and $\boldsymbol{2.107}$ respectively. However, both kaiming init losses are similar to the losses from fixing the saturated tanh layer. But the good thing now is that we didn't have to pick arbitrary numbers for the initialization scaling factors.

1.4. Batch Normalization¶

Batch normalization came out in 2015 by a Google team.

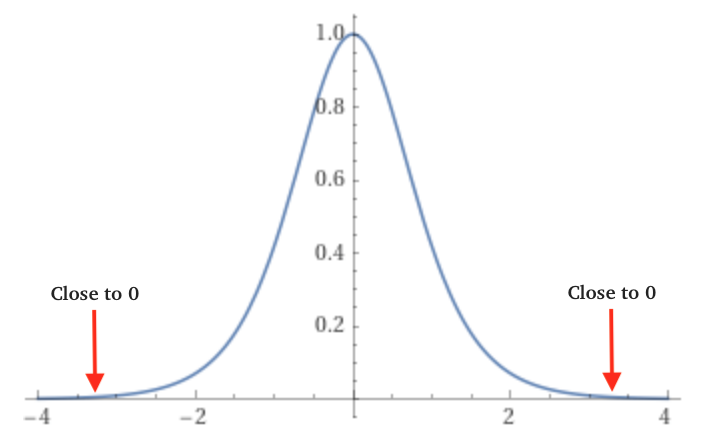

We don’t want the preactivations to be either too small or too large, because then our non-linearity either does nothing or gets saturated respectively. It destabilizes the network. To avoid this, we normalize the hidden state activations to be Gaussian in the batch. This normalization is a differentiable operation and thus can be used in neural networks. We want the activations to be Gaussian at initialization but then allow backpropagation to tell us how to move them around during training. We don’t want the distribution to be permanently constrained to a Gaussian shape. Ideally, we would allow the neural network to adjust this distribution, making it more diffuse or sharper, or allowing some tanh neurons to become more or less responsive. We want the distribution to be dynamic, with backpropagation guiding its adjustments.

Therefore, in addition to standardizing the activations at any point in the network, it’s also necessary to introduce a ‘scale and shift' component. This allows the model to undo the normalization if it determines that it’s better for the learning process. For this purpose, we introduce batch normalization gain and offset parameters, which are optimized during training, to scale and shift the normalized inputs respectively. Below is a figure showing the Batch Normalizing Transform, applied to activation $x$ over a mini-batch, $B{N}_{\gamma,\beta}({x}_{i})$

Figure 3. Batch Normalization Algorithm. (Source)

Figure 3. Batch Normalization Algorithm. (Source)

hpreact.shape

torch.Size([32, 200])

hpreact.mean(0, keepdim=True).shape, \

hpreact.std(0, keepdim=True).shape

(torch.Size([1, 200]), torch.Size([1, 200]))

# MLP revisited

n_embd = 10 # the dimensionality of the character embedding vectors

n_hidden = 200 # the number of neurons in the hidden layer of the MLP

g = torch.Generator().manual_seed(2147483647) # for reproducibility

C = torch.randn((vocab_size, n_embd), generator=g)

W1 = torch.randn((n_embd * block_size, n_hidden), generator=g) * (5/3) / ((n_embd * block_size)**0.5)

b1 = torch.randn(n_hidden, generator=g) * 0.01

W2 = torch.randn((n_hidden, vocab_size), generator=g) * 0.01

b2 = torch.randn(vocab_size, generator=g) * 0

bngain = torch.ones((1, n_hidden))

bnbias = torch.zeros((1, n_hidden))

parameters = [C, W1, b1, W2, b2, bngain, bnbias]

print(sum(p.nelement() for p in parameters)) # number of parameters in total

for p in parameters:

p.requires_grad = True

12297

# same optimization as last time

max_steps = 200000

batch_size = 32

lossi = []

for i in range(max_steps):

# minibatch construct

ix = torch.randint(0, len(Xtr), (batch_size,), generator=g)

Xb, Yb = Xtr[ix], Ytr[ix] # batch X, Y

# forward pass

emb = C[Xb] # embed characters into vector space

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # flatten (concatenate the vectors)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # hidden layer pre-activation

hpreact = bngain * (hpreact - hpreact.mean(0, keepdim=True))/hpreact.std(0, keepdim=True) + bnbias

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # hidden layer activation

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # output layer

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, Yb) # cross-entropy loss function

# backward pass

for p in parameters:

p.grad = None

loss.backward()

# update

lr = 0.1 if i < 100000 else 0.01 # step learning rate decay

for p in parameters:

p.data -= lr * p.grad

# track stats

if i % 10000 == 0: # print every once in a while

print(f'{i:7d}/{max_steps:7d}: {loss.item():.4f}')

lossi.append(loss.log10().item())

#break

0/ 200000: 3.3147 10000/ 200000: 2.1984 20000/ 200000: 2.3375 30000/ 200000: 2.4359 40000/ 200000: 2.0119 50000/ 200000: 2.2595 60000/ 200000: 2.4775 70000/ 200000: 2.1020 80000/ 200000: 2.2788 90000/ 200000: 2.1862 100000/ 200000: 1.9474 110000/ 200000: 2.3010 120000/ 200000: 1.9837 130000/ 200000: 2.4523 140000/ 200000: 2.3839 150000/ 200000: 2.1987 160000/ 200000: 1.9733 170000/ 200000: 1.8668 180000/ 200000: 1.9973 190000/ 200000: 1.8347

plt.plot(lossi)

plt.show()

We can view the loss across batches of 1000 and take the mean for every batch. The loss is dropping which is good!

torch.tensor(lossi).view(-1, 10000).mean(1)

tensor([0.3693, 0.3514, 0.3461, 0.3428, 0.3398, 0.3386, 0.3372, 0.3360, 0.3350,

0.3345, 0.3225, 0.3219, 0.3209, 0.3208, 0.3210, 0.3195, 0.3198, 0.3199,

0.3192, 0.3190])

plt.plot(torch.tensor(lossi).view(-1, 1000).mean(1));

@torch.no_grad() # this decorator disables gradient tracking

def split_loss(split):

x,y = {

"train": (Xtr, Ytr),

"dev": (Xdev, Ydev),

"test": (Xte, Yte),

}[split]

emb = C[x] # (N, block_size, n_embd)

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # (N, block_size * n_embd)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # (N, n_hidden)

hpreact = bngain * (hpreact - hpreact.mean(0, keepdim=True))/hpreact.std(0, keepdim=True) + bnbias

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # (N, n_hidden)

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # (N, vocab_size)

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, y)

print(f"{split} loss: {loss.item()}")

split_loss("train")

split_loss("dev")

train loss: 2.0668270587921143 dev loss: 2.104844808578491

With batch normalization, the training and validation losses decreased even further from $\boldsymbol{2.124}$ and $\boldsymbol{2.165}$ to $\boldsymbol{2.0668}$ and $\boldsymbol{2.1048}$ respectively. However, it doesn't necessarily improve on kaiming initialization and this is because of the simple nature of our neural network with only one hidden layer.

Tuning the scale of weight matrices of deeper neural networks with lots of different types of operations such that all the activations throughout the neural net are roughly gaussian will be extremely difficult, and become very quickly intractable. However, in comparison, it'll be much more easier to sprinkle batch normalization layers throughout the neural network. In neural networks, it's customary to append a batch normalization layer right after a linear/convolutional layer to control the scale of the activations throughout the neural network. It doesn't require the user to perform perfect mathematics or care about the activation distributions for all the building blocks the user might want to introduce into the neural network. It also significantly stabilizes the training.

Stability comes with a cost. In batch normalization, we mathematically couple the examples within a batch. The hidden states and logits for any example are no longer a function of that one example, but a function of all other examples that happen to be in the same batch. And that sample batches are randomly selected!

This coupling effect (2nd-order effect), despite its shortcomings, has a positive side. Padding out all the examples in the batch introduces a bit of entropy and this acts as a regularization. It's basically a form of data augmentation. As a result, it is harder to overfit these concrete examples. Other normalization techniques that don't couple the examples of a batch are layer, group and instance normalization.

Batch normalization requires that all examples be packaged in batches. But what do we do in inference mode when we usually feed only one example into the neural network? The solution is to compute the batch mean and standard deviation over the entire training set and use these parameters at inference time.

After deployment, the model should generate a single output for a single input. We should be able to forward a single example. At the end of the training, we will calculate the mean and standard deviation of the hidden activations $w.r.t$ the entire training data set and use it in the forward pass. The means and standard deviations will be used during inference.

As per the BatchNorm paper, we would like to have a step after training that calculates and sets the BatchNorm mean and standard deviation a single time over the entire training set. Let's calibrate the BatchNorm statistics:

# calibrate the batch norm at the end of training

with torch.no_grad():

# pass the training set through

emb = C[Xtr]

embcat = emb.view(emb.shape[0], -1)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 # + b1

# measure the mean/std over the entire training set

bnmean = hpreact.mean(0, keepdim=True)

bnstd = hpreact.std(0, keepdim=True)

@torch.no_grad() # this decorator disables gradient tracking

def split_loss(split):

x,y = {

"train": (Xtr, Ytr),

"dev": (Xdev, Ydev),

"test": (Xte, Yte),

}[split]

emb = C[x] # (N, block_size, n_embd)

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # (N, block_size * n_embd)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # (N, n_hidden)

# hpreact = bngain * (hpreact - hpreact.mean(0, keepdim=True))/hpreact.std(0, keepdim=True) + bnbias

hpreact = bngain * (hpreact - bnmean) / bnstd + bnbias

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # (N, n_hidden)

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # (N, vocab_size)

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, y)

print(f"{split} loss: {loss.item()}")

split_loss("train")

split_loss("dev")

train loss: 2.066890239715576 dev loss: 2.1049015522003174

However, nobody wants to evaluate the training mean and standard deviation of an entire dataset as a separate step. We want to calculate the mean and standard deviation of the entire training set, during the training time. Instead, we want to do it in a running manner directly during the training process as proposed in the BatchNorm paper. We can use running means and averages in the forward pass. The rolling sum method allows one to do this. Note that a small momentum factor in the rolling sum may not result in an accurate estimates due to large differences between batches.

It is very important to adjust the momentum factor $w.r.t$ batch size to ensure convergence of the running mean and standard deviation estimates to the actual mean and standard deviation over the entire training set. For example, a small batch size of 32 will have a higher variance in the mean and standard deviation across different batches; a momentum factor of 0.1 might not be sufficient for accurate estimation or proper convergence of the running parameters, and so we use a momentum factor of 0.001 instead.

# MLP revisited

n_embd = 10 # the dimensionality of the character embedding vectors

n_hidden = 200 # the number of neurons in the hidden layer of the MLP

g = torch.Generator().manual_seed(2147483647) # for reproducibility

C = torch.randn((vocab_size, n_embd), generator=g)

W1 = torch.randn((n_embd * block_size, n_hidden), generator=g) * (5/3) / ((n_embd * block_size)**0.5)

b1 = torch.randn(n_hidden, generator=g) * 0.01

W2 = torch.randn((n_hidden, vocab_size), generator=g) * 0.01

b2 = torch.randn(vocab_size, generator=g) * 0

bngain = torch.ones((1, n_hidden))

bnbias = torch.zeros((1, n_hidden))

bnmean_running = torch.zeros((1, n_hidden))

bnstd_running = torch.ones((1, n_hidden))

parameters = [C, W1, b1, W2, b2, bngain, bnbias]

print(sum(p.nelement() for p in parameters)) # number of parameters in total

for p in parameters:

p.requires_grad = True

12297

# same optimization as last time

max_steps = 200000

batch_size = 32

lossi = []

for i in range(max_steps):

# minibatch construct

ix = torch.randint(0, len(Xtr), (batch_size,), generator=g)

Xb, Yb = Xtr[ix], Ytr[ix] # batch X, Y

# forward pass

emb = C[Xb] # embed characters into vector space

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # flatten (concatenate the vectors)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # hidden layer pre-activation

bnmeani = hpreact.mean(0, keepdim=True)

bnstdi = hpreact.std(0, keepdim=True)

hpreact = bngain * (hpreact - bnmeani) / bnstdi + bnbias

with torch.no_grad():

bnmean_running = 0.999 * bnmean_running + 0.001 * bnmeani

bnstd_running = 0.999 * bnstd_running + 0.001 * bnstdi

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # hidden layer activation

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # output layer

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, Yb) # cross-entropy loss function

# backward pass

for p in parameters:

p.grad = None

loss.backward()

# update

lr = 0.1 if i < 100000 else 0.01 # step learning rate decay

for p in parameters:

p.data -= lr * p.grad

# track stats

if i % 10000 == 0: # print every once in a while

print(f'{i:7d}/{max_steps:7d}: {loss.item():.4f}')

lossi.append(loss.log10().item())

#break

0/ 200000: 3.3147 10000/ 200000: 2.1984 20000/ 200000: 2.3375 30000/ 200000: 2.4359 40000/ 200000: 2.0119 50000/ 200000: 2.2595 60000/ 200000: 2.4775 70000/ 200000: 2.1020 80000/ 200000: 2.2788 90000/ 200000: 2.1862 100000/ 200000: 1.9474 110000/ 200000: 2.3010 120000/ 200000: 1.9837 130000/ 200000: 2.4523 140000/ 200000: 2.3839 150000/ 200000: 2.1987 160000/ 200000: 1.9733 170000/ 200000: 1.8668 180000/ 200000: 1.9973 190000/ 200000: 1.8347

plt.plot(lossi)

plt.show()

We can view the loss across batches of 1000 and take the mean for every batch. The loss is dropping which is good!

torch.tensor(lossi).view(-1, 10000).mean(1)

tensor([0.3693, 0.3514, 0.3461, 0.3428, 0.3398, 0.3386, 0.3372, 0.3360, 0.3350,

0.3345, 0.3225, 0.3219, 0.3209, 0.3208, 0.3210, 0.3195, 0.3198, 0.3199,

0.3192, 0.3190])

plt.plot(torch.tensor(lossi).view(-1, 1000).mean(1));

# fairly similar mean and std values for batchnorm and batchnorm_running

(bnmean - bnmean_running).mean(), (bnstd - bnstd_running).mean()

(tensor(0.0012), tensor(0.0231))

@torch.no_grad() # this decorator disables gradient tracking

def split_loss(split):

x,y = {

"train": (Xtr, Ytr),

"dev": (Xdev, Ydev),

"test": (Xte, Yte),

}[split]

emb = C[x] # (N, block_size, n_embd)

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # (N, block_size * n_embd)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 + b1 # (N, n_hidden)

# hpreact = bngain * (hpreact - hpreact.mean(0, keepdim=True))/hpreact.std(0, keepdim=True) + bnbias

hpreact = bngain * (hpreact - bnmean_running) / bnstd_running + bnbias

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # (N, n_hidden)

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # (N, vocab_size)

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, y)

print(f"{split} loss: {loss.item()}")

split_loss("train")

split_loss("dev")

train loss: 2.06659197807312 dev loss: 2.1050572395324707

Let's dive into epsilon in the normalization step of the batch normalization algorithm in the equation below:

$$

\hat{x}_i \leftarrow \frac{x_i - \mu_B}{\sqrt{\sigma^2_B + \epsilon}}

$$

What is $\epsilon$ in the normalization step used for?

It is usually a very small fixed number (example: 1E-5 by default). It basically prevents a division by zero, in the case that the variance over a batch is exactly zero.

Note that biases become useless when batch normalization is applied. They are canceled when subtracting the mean at the batch normalization level and thus do not affect the rest of the calculation. Instead, we have a batch normalization bias that is responsible for biasing the distribution. Batch normalization layers are placed after the layers where multiplications happen.

A typical simple neural network unit block consists of a linear (or convolutional) layer, a normalization (batch) layer, and a non-linearity layer. Adding batch normalization allows you to control the scale of activations in your neural network and care less about its distributions in all the building blocks of your network architecture.

\begin{equation}

\textbf{Generic NN Unit Block:} \\

\text{Weight Layer (Linear/Convolutional)} \rightarrow \text{Normalization Layer (BatchNorm)}\rightarrow\text{Nonlinearity Function (tanh/ReLU)}

\end{equation}

1.5. Batch Normalization: Summary¶

Batch normalization is used to control the statistics of the neural network activations. It is common to sprinkle batch normalization across the neural networks. Usually, batch normalization layers are placed after layers that have multiplications such as linear/convolutional layers. Batch normalization internally has parameters for the gain and bias which are trained using backpropagation. It also has 2 buffers: the mean and the standard devation. The buffers are trained using a running mean update.

Steps of batch normalization explicitly:

- calculate mean of activations feeding into the batch-norm layer over that batch

- calculate standard deviation of activations feeding into the batch-norm layer over that batch

- center the batch to be unit gaussian

- scale and offset that centered batch by the learned gain and bias respectively

- Throughout the previous steps, keep track of the mean and standard deviation of the inputs so as to maintain the running mean and standard deviation which will later be used at inference to prevent re-estimation of mean and standard deviation all the time. This allows us to forward individual examples during testing phase

Batch Normalization can become computationally expensive, is a common source of bugs because it couples examples together and calculates distributions with respect to the other examples, and cannot be used for certain tasks as it breaks the independence between examples in the minibatch; but it’s useful because:

- It reduces the internal covariate shift and improves the gradient flow

- Batch normalization helps to mitigate the vanishing and exploding gradient problems by ensuring that the activations have approximately zero mean and unit variance. This normalization of inputs ensures that gradients flow more smoothly during backpropagation, making the optimization process more stable and enabling faster convergence.

- Batch normalization acts as a form of regularization by adding noise to the input of each layer. This noise, introduced by the normalization process, helps prevent overfitting by adding a small amount of randomness to the activations during training.

- Batch normalization makes neural networks less sensitive to the choice of initialization parameters and can increase the rate of learning to reach convergence faster.

# MLP revisited

n_embd = 10 # the dimensionality of the character embedding vectors

n_hidden = 200 # the number of neurons in the hidden layer of the MLP

g = torch.Generator().manual_seed(2147483647) # for reproducibility

C = torch.randn((vocab_size, n_embd), generator=g)

W1 = torch.randn((n_embd * block_size, n_hidden), generator=g) * (5/3) / ((n_embd * block_size)**0.5)

#b1 = torch.randn(n_hidden, generator=g) * 0.01

W2 = torch.randn((n_hidden, vocab_size), generator=g) * 0.01

b2 = torch.randn(vocab_size, generator=g) * 0

bngain = torch.ones((1, n_hidden))

bnbias = torch.zeros((1, n_hidden))

bnmean_running = torch.zeros((1, n_hidden))

bnstd_running = torch.ones((1, n_hidden))

# parameters = [C, W1, b1, W2, b2, bngain, bnbias]

parameters = [C, W1, W2, b2, bngain, bnbias]

print(sum(p.nelement() for p in parameters)) # number of parameters in total

for p in parameters:

p.requires_grad = True

12097

# same optimization as last time

max_steps = 200000

batch_size = 32

lossi = []

#epsilon = 1E-5

for i in range(max_steps):

# minibatch construct

ix = torch.randint(0, len(Xtr), (batch_size,), generator=g)

Xb, Yb = Xtr[ix], Ytr[ix] # batch X, Y

# forward pass

emb = C[Xb] # embed characters into vector space

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # flatten (concatenate the vectors)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 #+ b1 # hidden layer pre-activation

# BatchNorm layer

# -------------------------------------------------------------

bnmeani = hpreact.mean(0, keepdim=True)

bnstdi = hpreact.std(0, keepdim=True)

hpreact = bngain * (hpreact - bnmeani) / bnstdi + bnbias

with torch.no_grad():

bnmean_running = 0.999 * bnmean_running + 0.001 * bnmeani

bnstd_running = 0.999 * bnstd_running + 0.001 * bnstdi

# -------------------------------------------------------------

# Non-linearity

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # hidden layer activation

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # output layer

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, Yb) # cross-entropy loss function

# backward pass

for p in parameters:

p.grad = None

loss.backward()

# update

lr = 0.1 if i < 100000 else 0.01 # step learning rate decay

for p in parameters:

p.data -= lr * p.grad

# track stats

if i % 10000 == 0: # print every once in a while

print(f'{i:7d}/{max_steps:7d}: {loss.item():.4f}')

lossi.append(loss.log10().item())

#break

0/ 200000: 3.3239 10000/ 200000: 2.0322 20000/ 200000: 2.5675 30000/ 200000: 2.0125 40000/ 200000: 2.2446 50000/ 200000: 1.8897 60000/ 200000: 2.0785 70000/ 200000: 2.3681 80000/ 200000: 2.2918 90000/ 200000: 2.0238 100000/ 200000: 2.3673 110000/ 200000: 2.3132 120000/ 200000: 1.6414 130000/ 200000: 1.9311 140000/ 200000: 2.2231 150000/ 200000: 2.0027 160000/ 200000: 2.0997 170000/ 200000: 2.4949 180000/ 200000: 2.0199 190000/ 200000: 2.1707

plt.plot(lossi)

plt.show()

@torch.no_grad() # this decorator disables gradient tracking

def split_loss(split):

x,y = {

"train": (Xtr, Ytr),

"dev": (Xdev, Ydev),

"test": (Xte, Yte),

}[split]

emb = C[x] # (N, block_size, n_embd)

embcat = emb.view((emb.shape[0], -1)) # (N, block_size * n_embd)

hpreact = embcat @ W1 #+ b1 # (N, n_hidden)

# hpreact = bngain * (hpreact - hpreact.mean(0, keepdim=True))/hpreact.std(0, keepdim=True) + bnbias

hpreact = bngain * (hpreact - bnmean_running) / bnstd_running + bnbias

h = torch.tanh(hpreact) # (N, n_hidden)

logits = h @ W2 + b2 # (N, vocab_size)

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits, y)

print(f"{split} loss: {loss.item()}")

split_loss("train")

split_loss("dev")

train loss: 2.0674147605895996 dev loss: 2.1056838035583496

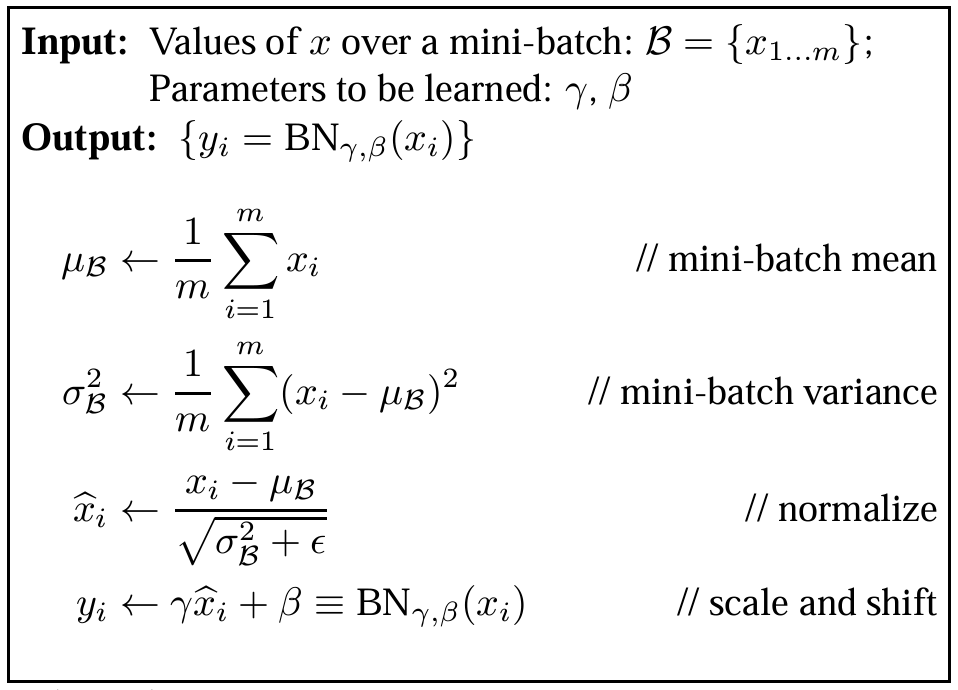

1.6. Real Example: ResNet50 Walkthrough¶

ResNet is a residual neural network for image classification, consisting of repeating "bottleneck blocks" that process input data through convolutional layers, batch normalization, and nonlinearity, ultimately leading to predictions about the image's contents. It was launched by Microsoft in 2015 with a design structure that was chosen specifically to address the vanishing/exploding gradient problem.

Figure 4. ResNet-34 Architecture. (Source)

The image is fed into the network, which consists of many layers with a repeating structure, ultimately leading to predictions about the image's contents. This repeating structure is made up of "bottleneck blocks" that are stacked sequentially. The code for these blocks initializes the neural network and defines how it processes input data through the forward pass. Convolutional layers are used for images, applying linear multiplication and bias offset to overlapping patches of the input. Batch normalization and nonlinearity, such as ReLU, are also applied in the network. For extremely deep neural networks, ReLU typically empirically works slightly better than tanh.

ResNet full PyTorch code implementation can be found in github. In the bottleneck block class module of the full code, the init function initializes the neural network and all its layers, and the forward function specifies the neural network's processing actions once all the inputs are ready. These actions include applying convolutional layers, batch normalization, nonlinearity function, and residual connections which we haven't covered yet. These blocks are basically replicated and stacked up serially. to form a Residual Network.

\begin{equation}

\textbf{Generic NN Unit Block:} \\

\text{Weight Layer (Linear/Convolutional)} \rightarrow \text{Normalization Layer (BatchNorm)}\rightarrow\text{Nonlinearity Function (tanh/ReLU)}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\textbf{Residual Network Unit Block:} \\

\text{Convolutional Layer} \rightarrow \text{Batch Normalization Layer} \rightarrow \text{ReLU}

\end{equation}

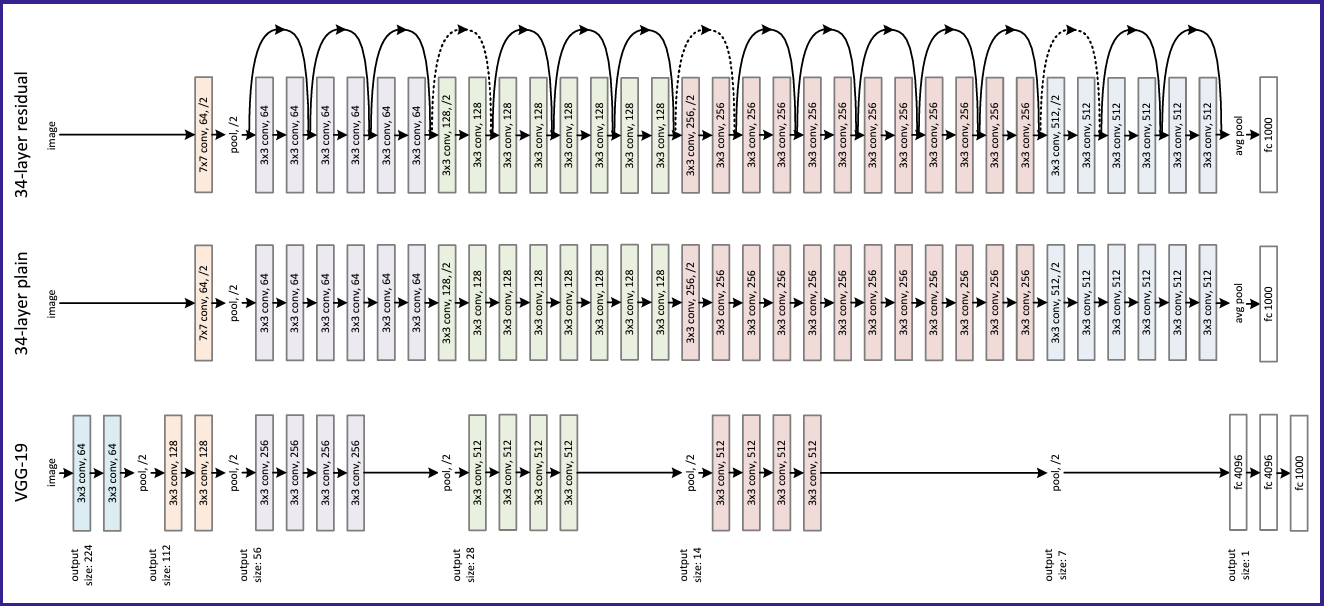

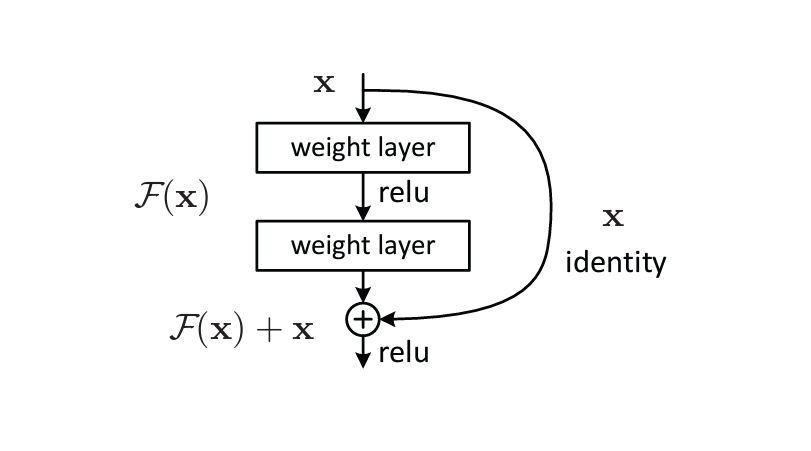

Figure 5. ResNet Bottleneck Unit Building Block. (Source)

ResNets utilize a technique called skip connections. Skip connections bypass intermediate layers, linking layer activations to subsequent layers. This forms a residual block. Stacking these residual blocks creates ResNets. The advantage of incorporating skip connections is that they allow regularization to bypass any layer that degrades the architecture's performance. As a result, training extremely deep neural networks becomes possible without encountering issues with vanishing or exploding gradients. Overall, ResNet uses a combination of convolutional layers, batch normalization, and nonlinearity to process images and make predictions about their contents.

1.7. Summary of the Lecture so far¶

So far, the lecture covered the challenge of scaling weight matrices and biases during neural network initialization to ensure that activations are roughly uniform throughout the network. This led to the development of the normalization layer, particularly the batch normalization layer, which allows for roughly Gaussian activations by centering the data using the mean and standard deviation. However, the layer has its complexities, such as needing to estimate the mean and standard deviation during training, and coupling examples in the forward pass of a neural net which causes several bugs. Hence, some recommended alternatives are group normalization or layer normalization.

This lecture covered the importance of understanding activations and gradients, and their statistics in neural networks, especially as they become larger and deeper. We saw how distributions at the output layer can lead to "hockey stick losses" if activations are not controlled, and how fixing this issue can improve training. We also discussed the need to control activations to avoid squashing to zero or exploding to infinity, and how this can be achieved by scaling weight matrices and biases during initialization.

The lecture then introduced the concept of normalization layers, specifically batch normalization, which helps achieve roughly Gaussian activations. Batch normalization works by centering and scaling data which are differentiable operations, but requires additional complexity to handle gain, bias, and inference. While influential, batch normalization can be problematic and has been largely replaced by alternatives like group normalization and layer normalization. The lecture concluded by highlighting the importance of controlling activation statistics, especially in deep neural networks.

In summary, the lecture emphasized the importance of understanding and controlling activations and gradients in neural networks, especially in deep networks. It introduced the concept of normalization layers, specifically batch normalization, which helps achieve roughly Gaussian activations. While batch normalization has been influential, it has limitations and has been largely replaced by alternatives. The lecture highlighted the importance of controlling activation statistics for good performance, especially in deep neural networks.

Next, we can move on to recurrent neural networks (RNNs). As we'll see, RNNs are essentially very deep networks, where you unroll the loop and optimize the neurons. This is where the analysis of activation statistics and normalization layers becomes crucial for good performance. We'll explore this in more detail in another notebook.

Summary of loss logs with forward pass activations improvements¶

- original:

- train loss: 2.1240577697753906

- dev loss: 2.165454626083374

- fix softmax confidently wrong:

- train loss: 2.0696

- dev loss: 2.1310

- fix

tanhlayer too saturated at init:- train loss: 2.0355966091156006

- dev loss: 2.1026785373687744

- use semi-principled "kaiming init" instead of hacky init:

- train loss: 2.0376644134521484

- dev loss: 2.106989622116089

- add batch norm layer:

- train loss: 2.06659197807312

- dev loss: 2.1050572395324707

1.8. PyTorch-ifying the Code¶

Let's build the complete code in PyTorch. Below is a list of the Kaiming initialization parameters:

fan_inis the number of input neuronsfan_outis the number of output neurons

Here are the BatchNorm layer initialization parameters:

dim: The dimensionality of the input tensor to be normalized.eps: A small value added to the denominator to avoid division by zero. Default value is set to $1\times10^{-5}$momentum: The momentum value used to update the running mean and variance during training. Default value is set to $0.1$

And these are the rest of the BatchNorm instance attributes:

training: A boolean flag indicating whether the batch normalization layer is in training mode.gamma: Parameter tensor representing the scale factors, initialized to ones.beta: Parameter tensor representing the shift factors, initialized to zeros.running_mean: Buffer tensor for storing the running mean of activations.running_var: Buffer tensor for storing the running variance of activations.

# SUMMARY + PYTORCHIFYING -----------

# Let's train a deeper network

# The classes we create here are the same API as nn.Module in PyTorch

class Linear:

def __init__(self, fan_in, fan_out, bias=True):

self.weight = torch.randn((fan_in, fan_out), generator=g) / fan_in**0.5

self.bias = torch.zeros(fan_out) if bias else None

def __call__(self, x):

self.out = x @ self.weight

if self.bias is not None:

self.out += self.bias

return self.out

def parameters(self):

return [self.weight] + ([] if self.bias is None else [self.bias])

class BatchNorm1d:

def __init__(self, dim, eps=1e-5, momentum=0.1):

self.eps = eps

self.momentum = momentum

self.training = True

# parameters (trained with backprop)

self.gamma = torch.ones(dim)

self.beta = torch.zeros(dim)

# buffers (trained with a running 'momentum update')

self.running_mean = torch.zeros(dim)

self.running_var = torch.ones(dim)

def __call__(self, x):

# calculate the forward pass

if self.training:

xmean = x.mean(0, keepdim=True) # batch mean

xvar = x.var(0, keepdim=True) # batch variance

else:

xmean = self.running_mean

xvar = self.running_var

xhat = (x - xmean) / torch.sqrt(xvar + self.eps) # normalize to unit variance

self.out = self.gamma * xhat + self.beta

# update the buffers

if self.training:

with torch.no_grad():

self.running_mean = (1 - self.momentum) * self.running_mean + self.momentum * xmean

self.running_var = (1 - self.momentum) * self.running_var + self.momentum * xvar

return self.out

def parameters(self):

return [self.gamma, self.beta]

class Tanh:

def __call__(self, x):

self.out = torch.tanh(x)

return self.out

def parameters(self):

return []

n_embd = 10 # the dimensionality of the character embedding vectors

n_hidden = 100 # the number of neurons in the hidden layer of the MLP

g = torch.Generator().manual_seed(2147483647) # for reproducibility

C = torch.randn((vocab_size, n_embd), generator=g)

# layers = [

# Linear(n_embd * block_size, n_hidden, bias=False), BatchNorm1d(n_hidden), Tanh(),

# Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden, bias=False), BatchNorm1d(n_hidden), Tanh(),

# Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden, bias=False), BatchNorm1d(n_hidden), Tanh(),

# Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden, bias=False), BatchNorm1d(n_hidden), Tanh(),

# Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden, bias=False), BatchNorm1d(n_hidden), Tanh(),

# Linear( n_hidden, vocab_size, bias=False), BatchNorm1d(vocab_size),

# ]

layers = [

Linear(n_embd * block_size, n_hidden), Tanh(),

Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden), Tanh(),

Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden), Tanh(),

Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden), Tanh(),

Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden), Tanh(),

Linear( n_hidden, vocab_size),

]

# layers = [

# Linear(n_embd * block_size, n_hidden),

# Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden),

# Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden),

# Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden),

# Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden),

# Linear( n_hidden, vocab_size),

# ]

with torch.no_grad():

# last layer: make less confident

#layers[-1].gamma *= 0.1

layers[-1].weight *= 0.1

# all other layers: apply gain

for layer in layers[:-1]:

if isinstance(layer, Linear):

layer.weight *= 5/3

parameters = [C] + [p for layer in layers for p in layer.parameters()]

print(sum(p.nelement() for p in parameters)) # number of parameters in total

for p in parameters:

p.requires_grad = True

46497

# same optimization as last time

max_steps = 200000

batch_size = 32

lossi = []

for i in range(max_steps):

# minibatch construct

ix = torch.randint(0, Xtr.shape[0], (batch_size,), generator=g)

Xb, Yb = Xtr[ix], Ytr[ix] # batch X,Y

# forward pass

emb = C[Xb] # embed the characters into vectors

x = emb.view(emb.shape[0], -1) # concatenate the vectors

for layer in layers:

x = layer(x)

loss = F.cross_entropy(x, Yb) # loss function

# backward pass

for layer in layers:

layer.out.retain_grad() # AFTER_DEBUG: would take out retain_graph

for p in parameters:

p.grad = None

loss.backward()

# update

lr = 0.1 if i < 100000 else 0.01 # step learning rate decay

for p in parameters:

p.data += -lr * p.grad

# track stats

if i % 10000 == 0: # print every once in a while

print(f'{i:7d}/{max_steps:7d}: {loss.item():.4f}')

lossi.append(loss.log10().item())

break # AFTER_DEBUG: would take out obviously to run full optimization

0/ 200000: 3.7561

2. Visualizations¶

IMPORTANT: For each plot below, ensure the appropriate gain is properly defined in the prior cells. For the fully linear case (no Tanh, be sure to update layers) !!!¶

- gain changes for diagnostic study of forward pass activations and backward gradient activations

with torch.no_grad():

# last layer: make less confident

layers[-1].weight *= 0.1

# all other layers: apply gain

for layer in layers[:-1]:

if isinstance(layer, Linear):

layer.weight *= 5/3 #change accordingly for diagnostic study

- Fully linear case with no non-linearities (no

Tanh)

layers = [

Linear(n_embd * block_size, n_hidden), #Tanh(),

Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden), #Tanh(),

Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden), #Tanh(),

Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden), #Tanh(),

Linear( n_hidden, n_hidden), #Tanh(),

Linear( n_hidden, vocab_size),

]

Re-initialize layers and parameters in section 1.8 (re-run both cells there) using the above changes before running the cells below¶

2.1. Forward Pass Activation Statistics¶

Let's visualize the histograms of the forward pass activations at the tanh layers. We're using a tanh layer because it has a finite output range $\boldsymbol{[-1, 1]}$ which is very easy to work with. Also the gain for tanh is $\boldsymbol{5/3}$.

layer.weight *= 5/3

# visualize histograms

plt.figure(figsize=(20, 4)) # width and height of the plot

legends = []

for i, layer in enumerate(layers[:-1]): # note: exclude the output layer

if isinstance(layer, Tanh):

t = layer.out

print('layer %d (%10s): mean %+.2f, std %.2f, saturated: %.2f%%' % (i, layer.__class__.__name__, t.mean(), t.std(), (t.abs() > 0.97).float().mean()*100))

hy, hx = torch.histogram(t, density=True)

plt.plot(hx[:-1].detach(), hy.detach())

legends.append(f'layer {i} ({layer.__class__.__name__})')

plt.legend(legends);

plt.title('activation distribution');

layer 1 ( Tanh): mean -0.02, std 0.75, saturated: 20.25% layer 3 ( Tanh): mean -0.00, std 0.69, saturated: 8.38% layer 5 ( Tanh): mean +0.00, std 0.67, saturated: 6.62% layer 7 ( Tanh): mean -0.01, std 0.66, saturated: 5.47% layer 9 ( Tanh): mean -0.02, std 0.66, saturated: 6.12%

The first layer is fairly saturated ($\boldsymbol{\sim20\%}$). However, later layers become stable due to our initialization. This is because we multiplied the weights by a gain of $\boldsymbol{5/3}$. However, if we use a gain of $1$, we can observe the following scenario.

layer.weight *= 1

# visualize histograms

plt.figure(figsize=(20, 4)) # width and height of the plot

legends = []

for i, layer in enumerate(layers[:-1]): # note: exclude the output layer

if isinstance(layer, Tanh):

t = layer.out

print('layer %d (%10s): mean %+.2f, std %.2f, saturated: %.2f%%' % (i, layer.__class__.__name__, t.mean(), t.std(), (t.abs() > 0.97).float().mean()*100))

hy, hx = torch.histogram(t, density=True)

plt.plot(hx[:-1].detach(), hy.detach())

legends.append(f'layer {i} ({layer.__class__.__name__})')

plt.legend(legends);

plt.title('activation distribution');

layer 1 ( Tanh): mean -0.02, std 0.62, saturated: 3.50% layer 3 ( Tanh): mean -0.00, std 0.48, saturated: 0.03% layer 5 ( Tanh): mean +0.00, std 0.41, saturated: 0.06% layer 7 ( Tanh): mean +0.00, std 0.35, saturated: 0.00% layer 9 ( Tanh): mean -0.02, std 0.32, saturated: 0.00%

The saturation drops to $\boldsymbol{0\%}$. However, the standard deviation is also shrinking, thus, converging the whole distribution to zero. The tanh function squeezes the distribution. Thus, we need sufficient gain to fight the shrinking/squashing.

Let's try a gain of $\boldsymbol{3}$.

layer.weight *= 3

# visualize histograms

plt.figure(figsize=(20, 4)) # width and height of the plot

legends = []

for i, layer in enumerate(layers[:-1]): # note: exclude the output layer

if isinstance(layer, Tanh):

t = layer.out

print('layer %d (%10s): mean %+.2f, std %.2f, saturated: %.2f%%' % (i, layer.__class__.__name__, t.mean(), t.std(), (t.abs() > 0.97).float().mean()*100))

hy, hx = torch.histogram(t, density=True)

plt.plot(hx[:-1].detach(), hy.detach())

legends.append(f'layer {i} ({layer.__class__.__name__})')

plt.legend(legends);

plt.title('activation distribution');

layer 1 ( Tanh): mean -0.03, std 0.85, saturated: 47.66% layer 3 ( Tanh): mean +0.00, std 0.84, saturated: 40.47% layer 5 ( Tanh): mean -0.01, std 0.84, saturated: 42.38% layer 7 ( Tanh): mean -0.01, std 0.84, saturated: 42.00% layer 9 ( Tanh): mean -0.03, std 0.84, saturated: 42.41%

Now, the saturation is too high and does not converge to zero. Ultimately, a gain of $\boldsymbol{5/3}$ is the most suitable as it stabilizes the sandwich of Linear and Tanh layers and limits the saturation to a good low range ($\sim5\%$).

2.2. Backward Pass Gradient Statistics¶

Let's visualize the histograms of the backward pass gradient at the tanh layers. First, let's use a gain of $\boldsymbol{5/3}$.

# visualize histograms

plt.figure(figsize=(20, 4)) # width and height of the plot

legends = []

for i, layer in enumerate(layers[:-1]): # note: exclude the output layer

if isinstance(layer, Tanh):